S.J.A. Turney - Praetorian: The Great Game, Mulcahy Books, 2015

Having become a big fan of Simon's Marius' Mules series, I have been privileged enough to read Praetorian: The Great Game, his latest book, before its launch yesterday.

Coming at it from halfway through the Fronto saga I expected, with reasonable variation, more of the same. And it is more of the same in some very broad aspects: historical fiction, based on historical facts and set in the Roman Empire, with the same insane level of documentation and detail, so very accurate that it is impossible to catch the author off-guard, save maybe for a few debatable turns of phrases.

But in many other regards it is a completely different type of book. And the most striking difference is that, while the adventures of Caesar's army in Gaul is a story of truly epic proportions, comprising a vast number of characters, huge armies and battles that became turning points in history, Praetorian is mostly an individual story. It is, if you want, Ulysses' Odyssey to the all-encompassing Illiad. Schindler's List vs Saving Private Ryan, if we're talking WWII movies. Or, to put it otherwise: if I'd entrust Ridley Scott to direct the MM series, then Praetorian would be best served by Martin Scorsese.

The story is set two centuries later than Fronto's, and the events in-between have greatly transformed the Roman world. If there would be such a thing as Outstanding Achievement in Historical Description Award, then Simon would be well deserving of one because, while I can't put my finger on what exactly it is that does it, there is a completely different picture of Praetorian's Rome as opposed to MM Rome. I am not versed enough in Roman history, nor traveled enough to know how different high imperial Rome would have been from late republican Rome, but this book teaches a great deal, and I have come to learn Simon's words are mostly to be believed.

It is probably unfair to speak about Praetorian exclusively in comparison terms, but it will be unavoidable, seeing that the writer has been bold enough to approach an era so brilliantly depicted in the multiple Oscar winner The Gladiator, and from an entirely different angle. The main historical characters are the same in the two (Marcus Aurelius, Commodus, Lucilla), but in the book they all are everything they are not in the movie. Now, it is a tendency of artistic enterprises to steer the public's opinion towards a simplistic classification of characters or facts in categories. We need a good guy and a bad guy for any sort of drama. So in describing Nero the emperor, for instance, one can either walk the beaten path and consider him a mindless tyrant or go against the current and find some episode or story that would put him in a good light, earning him if not redemption, at least an excuse.

Usually, however, reality is more complicated than what human mind can achieve and classifying historical figures as good or bad is actually detrimental to the science of history. All deeds are contextual, everyone is a man of their time and there is never any telling about any historical figure thought process. We can read Caesar's books, judge his facts and speculate as to his reasons, but it will always be impossible to tell how much he wanted the good of the republic or how heroic the Battle of Alesia was, for instance.

The beauty of fiction, however, is that can fill the gaps in research however the author sees fit. Ridley Scott's Marcus Aurelius is assassinated by his son, while Simon's Commodus is nothing but a loving son and rightful heir. And both can be equally right. Neither Marcus Aurelius, nor Commodus were good or bad, but they were both part of a great game, bigger even than the one Praetorian talks about.

And I was glad to see there is no talk of a decline of the Empire in Praetorian, the obsession of find the high point of Roman history, the one where decline started, being in my opinion an unhealthy one, and one that has driven historians over two millennia to place this high point anywhere between the Punic Wars and the Odoacer kingship.

Before he gets to the main stage of history, however, we find our hero, Gnaeus Marcius Rustius Rufinus, in the Pannonic forests chasing defeated Marcomanni in a scene that made me think Praetorian might well beat the body count of all the MM series. It doesn't, in the end, as the focus goes quickly away from Legio X Gemina and goes to our young hero and his adventures that - incredulous as they might seem - could just be true. Rufinus will end up a Praetorian Prefect under Caracalla, but until then we'll have to wait a few more years and a few more books. The Great Game only sees the young Rufinus through the last days of Marcus Aurelius - who he gets to meet briefly - and up to the plot against Commodus in 182 AD. It's a way of saying, sees him through, given that he is, more often than not, in the very core of the events, though always in the background and mostly in the stealth. Because our hero is very much an avant la lettre James Bond, down to a t, and this book is mostly a book of espionage.

On His Majesty's secret service, young Argentulum gets involved in plots for which the world is not enough. He gets more than a view to a kill, a licence to kill himself and gets to only live twice thanks to Pompeianus' medicus (probably a Dr. No, though not specified) who enables him to die another day and play a further part in the great game of dice royale. The metaphor of the hasta pura as a gold finger is brilliant, The hasta pura is forever, and Rufinus is the man with the silver gun in the key scene, where he lives and lets die. Oh , I could go on forever, There are even Bond girls - his only quantum of solace, perhaps? - and Senova the Briton can testify as to the Praetorian who loved her. From Rome with love, by Simon Turney, who I'd like to see denying the Bond influence on this book.

There are only a couple of other things I can say without giving too much of the plot away: if you liked Connie Nielsen's depiction of Lucilla (I loved it), be prepared for nothing of the same. Commodus' sister is, despite her brief appearances, a central character portrayed mostly in a negative space style. Her presence is always felt, but she is rarely there. Villa Hadriana, the same beautiful arrangement of rocks and gardens it has always been, provides the stage for the story and its rich description put it up second on the list of places I want to see in Rome (first place, Tajan's column, is hard to beat).

In a very Elisabethan turn of events, there's even a dog. Well, two dogs, but... you'll see. And rarely - if ever - have I seen more depth in a non-human character than here. Jungle Books and other personifications don't count.

I'm tempted to say Praetorian is a more accomplished book than Marius' Mules, but when it comes down to the small details, I find that hard to judge. Style always evolves, and the comparison might be unfair to MM, seeing that The Invasion of Gaul was Simon's first ever novel. The feeling his, with Praetorian, Simon is running against history much less. There is no detailed first hand account of the facts here like the rigid scaffolding of De Bello Gallico is for MM. And he seems to be enjoying this liberty, using each piece of hard information more like a trampoline for new subplots rather than a limitation. There are, of course, big spoilers all over the place (Marcus Aurelius will die, Commodus will become emperor), but they do not seem to be taking away any of the joy of the lecture. If anything, it is the author who gives away too much, like a director too delighted with the footage trying to fit it all in final cut.

A seemingly random scene in the book sees Praetorian Prefect Paternus meeting three senators, Publius Helvius Pertinax amongst them. I knew then we will hear more about this guy, although he does not make another appearance in The Great Game. Which only means there will be more to come. I am looking forward to Praetorian II and mostly, I am looking forward to see Rufinus through the very difficult and delicate year of the five emperors.

People familiar with Simon's works will probably need no convincing to read The Praetorian. For the rest, the book will take you down a deep rabbit hole which you'll only wish deeper. And I'm afraid Simon only writes 2-3 books a year, far too little to quench the readers' thirst, although an insanely prolific rate given the quality of the writing.

"If you hope to do any good, the first rule is that you have to survive long enough to do it." Pompeianus' tells Rufinus. Well, young man, you have at least another 35 years.

Now, regardless of how you got here, you should know this review is part of a blog tour that started yesterday, when the book was launched, with an author's introduction. It will continue tomorrow with an account about writing historical locations here. And it even has a banner. Which I think is brilliant, an am honoured to be a part of. Here:

vineri, 13 martie 2015

sâmbătă, 7 martie 2015

Constable Fronto

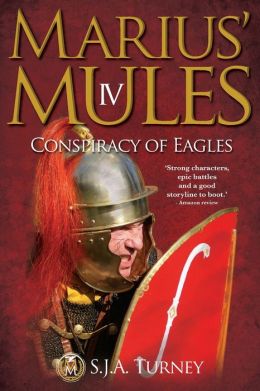

S.J.A. Turney - Marius' Mules IV: Conspiracy of Eagles, Victrix Books, 2013

After catching my attention with the first book in the series, finding his feet and going all out with some wonderful battle scenes in the second and then rounding the story up with more of the same plus an in-depth exploration of characters and background stories in a peaking third book, I thought the fourth book drops the standard a little bit. After all, Caesar's fourth year in Gaul makes for some great reading, epic scenes and much of the world history being made: first advent of an organized Roman force North of the Rhine, first Roman military expedition to the British Isles and the year in which Trans-alpine Gaul is referred to as a Roman province in Rome. So naturally, I expected Conspiracy of Eagles to flesh all of these out. Instead of sticking to the beaten track, Simon makes some very unexpected choices.

The last book, Gallia Invicta, already saw two of everyone's favourite Romans, Lucius Vorenus and Titus Pullo, given less space than even Caesar in his concise reports thought necessary, and that was unexpected. Understandable though, as probably Simon did not want to delve into similar story lines with HBO series' Rome. But with Conspiracy of Eagles, most of my guesses about the focal points of the book have gone astray. Crossing of the Rhine, and the magnificent bridge Caesar was so proud of that he took the time to describe in detail the building process? Rather briefly dismissed by Simon, who instead takes Fronto across on a different route and would have probably made him conquer Germania all by himself, had Caesar not decided to leave quickly. Attack on the British Isles? Hmm, this was a tricky one. No character, not even Julius Caesar, the man who stood in front of Alexander's statue and measured his achievements against the great warrior's, have any sense of history or majesty, which would be the first thing in my mind. With a visible affection for his native land, Simon opts for a very tongue in cheek description of the South East coast, one that - although entirely accurate and well documented - has become the funniest cliche I've ever encountered: while in Spain the rain falls mostly on the plain, in Britain the rain falls everywhere, all the time. So much so that there are numerous words in English referring to rain that a language like Italian has an awful time translating. I remembered reading the letters of Roman legionaries in Britain at the British Museum, most of which were full of complaints about the weather and requests for warmer clothes, and that sentiment was fully echoed here.

There is some more attention paid to this first, largely unsuccessful incursion in England, but the focus is always some place else. While the battle scenes are as gripping as ever, the reader's main focus goes back to an intricate web of conspiracies, politics and personal dramas that puts Britain in the background. I expected Simon to put all the blame for the ill-planned expedition at Caesar's feet, but in hindsight it would have been all too easy.

And then finally, in the last few chapters of the book, I surrendered to the idea that this is no longer a historical novel but rather a policier set in ancient Rome. As soon as I did that, the book appeared in a very different light, and Simon proved (once again) to be as masterful a writer with criminal investigations and espionage as he is with battles and sieges. The cherry on the cake is a plot twist at the very end of the book that only left me wanting for more. Luckily, there is more and this time I will expect nothing from the fifth book. No druids, war chariots or pict archers, no masterclass in sailing from one of the few glorious chapters of triumph at sea in Roman history and no expectation from Caesar whatsoever. I have obviously grown very fond of Fabius and Furio (although I still can't really make them apart), so naturally I'd like to hear more of them. Not very sure I will though.

And then there are some big questions that lie in waiting to which probably Simon only has a sketch of an answer as of yet: what of the Civil War? Will a married Fronto be willing to carry on fighting? Moreover, will he be still supporting Caesar when he takes on Rome? What of Labienus, of which we know for sure fought for Pompei? At which point the rift between him and the general will pass the point of no return? Will death, from which Fronto has escaped so many times, finalli find him on the battlefield, or will he see off his days in the warm sun of Southern Italy? Well, there's three more years of campaigning before we get any closer to the answer.

Some web reviews of Marius' Mules seem to protest against the modern elements in the language. I have raised this point in my review of the first book. Some of it is justified (yes, to bury the hatchet is a expression gifted, together with the Americas, by the pre-Columbian natives and yes, the language does put the novels in a modern context, enabling readers of the future to easily identify the time of writing), but none of it matters for the author's enterprise. The series still stands as an amazing introduction to the Roman world and to a series of legendary figures of heroes and super-heroes who have the capes and the money, but lack the batmobiles, extraterrestrial birth or gene changing accident. I am more concerned about reintroducing the characters each time they appear in a book by their deeds and achievements in the previous books. It gives the series one of the most disturbing traits in the TV documentaries of today: the assumption that the audience are too dumb to follow a point if it's not stressed every ten minutes and that they need to be reminded about the matter at hand after each advertisement break, because they all have the attention span of a goldfish.

One historical point to address: there are a number of references to the wolf standard as symbol of the cavalry. I have raised this point to Simon and luckily he said they stem not from historical references but from personal preference. Which was fortunate for me because it spared me hours of re-reading of sources. As a Romanian, I hold the wolf standard as an important symbol and take some pride in the fact it was adopted by the Roman cavalry after the conquest of Dacia. While it is not exclusively a Dacian symbol, there is no record of its official use in the Roman army before the second century after the Empire.

And a quote I particularly liked: "It [politics] won't bother you, I suppose. You've been given a sword and pointed at a barbarian." says Fronto to the two centurions in the discussion on the beach. This resembles another favourite quote of mine, written by Antony Minghella for WP Inman, the Civil War soldier who says he's been sent to war, like countless others, with a lie and a flag. Both phrases echo a larger truth, the fact that wars are essentially useless, a horror for soldiers and civilians alike, from which a handful of political heads profit. But, gosh, there is something so terribly attractive about wearing a sword and a shield!

Abonați-vă la:

Comentarii (Atom)